The Gravest Injustice

By Nikki Meredith

Sexually abused children feel ashamed and guilty about their experiences, and this may prompt them to block the memory.

The number of reported child abuse cases is up 2,000 percent, yet few cases ever reach the courts, and fewer still resulting in convictions. Why is our legal system failing us?

For those of us who do not feel sexual urges toward children, the recent explosion of news reports about child sexual abuse has had a stunning, almost unreal effect. The idea that there is a sizable subterranean world of normal-seeming people who violate the bodies and minds of young children for their own gratification does not fit with what we know about civilized society. To believe even half the reports in the press about increased child molestation is to accept something so gloomy about humanity that it’s tempting to think, as many people do, that the problem must be greatly exaggerated, a delusion peculiar to overzealous prosecutors and hysterical parents.

And yet the facts are there.

According to the National Committee for Prevention of Child Abuse, incidences of reported sexual abuse of children of all ages have risen 2,000 percent during the past decade. And the largest increase is among children under seven, many of whom are molested in daycare or other out-of-home environments. Though most sexually abused children are molested by members of their own families (8.9 out of every 10,000 children), 5.5 of every 10,000 children are abused by nonrelatives, adults who in many cases are entrusted with their care. The steep rise in reported instances of abuse is due in part to increased disclosure, thanks to more attention being given to the issue by public programs and the media. But most experts believe that there is more abuse now than in years past, largely because greater numbers of children are living with stepparents, and more young children are under the supervision of daycare workers and babysitters.

The statistics indicate a growing danger – a source of considerable alarm to parents. This fear, coupled with the disturbing fact that most attempts to prosecute sexual abusers fail for reasons that don’t always exonerate the accused, has created a climate that is almost as troubled as the lives of the young victims themselves.

To better understand the expanding scope of child sexual abuse, researchers have turned their inquiries to the abusers. Last year, psychiatrist Gene G. Abel of the Behavioral Medicine Institute in Atlanta, Georgia, completed an eight-year study for the National Institute of Mental Health involving 561 men with psychosexual disorders. The men interviewed were living in four different cities, and most of them have never been incarcerated. Of the group, 403 have admitted to sexually abusing children. It is the largest study of its kind ever conducted of men who are living freely in the community.

Researchers were astounded at the large numbers of children the men reported molesting: among the 403 men, a total of 67,000 children had been abused. (This total encompassed all criminal sexual behavior against children; 38,000 children had been abused to the point of being touched.) The other surprise was the high number of boys who were molested. When researchers looked at the total number of children molested – including those who were not touched but were the objects of such offenses as indecent exposure and voyeurism – little girls were molested most often. But when they looked at the more serious offenses – ones in which the children were touched – they found that 63 percent of the children who were sexually assaulted were little boys. The men who molested them reported an average of 282 victims each while the men who physically molested little girls reported an average of 23 victims each.

The study also challenged some long-held notions about sex offenders. In the past, researchers have made a distinction between pedophiles – men who are primarily and almost always exclusively attracted to children – and “regressed” child molesters, who may have normal adult relationships but during periods of stress will pursue children. Generally, pedophiles are considered inadequate personality types who are unmarried and have few adult relationships. In Abel’s study, however, these distinctions were blurred. Nearly 80 percent of the men who molested young boys were heterosexual and most were married and had children.

Based on the study’s findings, the typical child molester is Caucasian, male, 20 to 40 years old, well educated, and holds a full-time job. He is usually married, with children of his own whom he typically does not molest. Most often, he is a well respected member of his community. He only assaults children with whom he has built up a trusting relationship.

Another recent, unexpected development in the news about child sexual abuse has been the increase in the number of reported cases involving women. A new national study by the University of New Hampshire-based Family Research Laboratory revealed that in 270 documented sex abuse cases involving more than 1,500 children in licensed daycare facilities, more than 40 percent of the sex offenders were women. Since this is such a new area of research, very little is known about female sexual offenders; before, it was thought that women who molested children only did so at the bidding of a domineering male.

“I’m a feminist, and I was very happy five years ago to think that women didn’t do this,” says Eileen Treacy, a New York child development expert who specializes in sexual abuse problems. “But my cases come from ten different counties, and I’m getting an increasing number of female offenders, particularly in daycare settings.” She recently completed an analysis of 133 of her cases and found that 38 percent of the boys and 17 percent of the girls were molested by women. “It’s out there. We just didn’t know about it before.”

Easily the most baffling and most frightening group of child molesters are those associated with ritualistic behavior. Incredible as it seems, increasing numbers of children, some as young as two or three years old, have come forward with harrowing tales of rituals that involve cannibalism, animal sacrifice, and group sex. When these accounts first started trickling in, even the most committed child advocates believed that they were more imagined than real. However, after hearing similar stories from literally hundreds of children from different parts of the country, as well as from adult victims of ritual abuse, many specialists are now convinced that the childrens’ stories are valid. Sandi Gallant, an intelligence officer with the San Francisco Police Department and one of the nation’s foremost experts on ritualistic crimes, says 40 to 60 “solid” cases of ritual sexual abuse have come to the attention of law enforcement officials in the past few years nationwide.

“What is striking about these cases,” says psychiatrist Roland Summit of Torrance, California, an expert on child sexual abuse, “is that children are telling stories so similar to each other. Their descriptions of ritual cult practices come out of nowhere in their backgrounds.”

Recently, several celebrated cases have involved allegations of ritualistic abuse and when the cases have run into difficulties in court – often partly because of these fantastic stories – they have been pointed to as proof that the whole child sexual abuse phenomenon is, quite literally, a witch hunt. One of the most publicized is the McMartin case in Manhattan Beach, California, a small town near Los Angeles. In the fall of 1983, a mother’s discovery that her two-year-old son had rectal bleeding after attending McMartin Preschool led to interviews of 380 children and the indictment on sexual charges of school founder Virginia McMartin, her daughter, grandson, and granddaughter and three other teachers. Included in the children’s testimony were stories of satanic worship, sexual, blood, and scatological rituals performed by black-robed adults. Although the judge who presided over the 18-month preliminary hearing ordered that there was enough evidence for the seven defendants to stand trial, newly elected Los Angeles district attorney Ira Reiner announced that five of the seven defendants would not be prosecuted because of insufficient evidence.

The problems in the McMartin case reflect problems in similar cases across the country. In Jordan, Minnesota; Bakersfield, California; and in Chicago’s Northside, children reported similar stories. In each of these cases, prosecutors were attacked because of the interviewing techniques employed by police investigators and therapists. In dismissing charges against five of the seven defendants in the McMartin case, Reiner criticized the therapists who had interviewed the children. “They would ask if the kids were touched in a yucky place by a bad teacher. If the kid said ‘No,’ they would say, ‘All your friends told us it happened and you’re just as smart as they are.'” Such accusations of interviewer manipulation have had a chilling effect on the whole field of child abuse investigation.

The techniques of child abuse investigation were initiated a little over 25 years ago, when astute pediatricians began tracking patterns of bone fractures in their patients that could only be explained by beatings, not by the he-fell-down-the-stairs stories offered by parents and guardians. Their identification of the battered-child syndrome brought about an awareness that children who are victimized, especially those who are the most brutally victimized, are not inclined to talk about it.

As clinicians learned how to talk to children in a language that children could understand, more and more stories of sexual abuse emerged. But as the number of stories increased, so did the public suspicions that children were not telling the truth, and child advocates developed the defensive and simplistic “children-never-lie” response.

Therapists and police investigators who specialize in the area of child sexual abuse now know that children do sometimes lie, children sometimes misperceive, and children often have trouble saying exactly what they mean. Accordingly, evaluation techniques have become more refined, and people who work with children are better equipped to discern the truth. For example, specially trained social workers or child psychologists know how to determine if a child was actually molested, or if he’s reconstructing something he heard from an older sibling or saw on an X-rated video. However, translating that knowledge of how children think to an adult criminal justice system continues to be problematic. According to a report released by the National Institute of Justice, because of the difficulty of proving the charges, and because of the very young ages of some of the victims, 90 percent of all known child sexual abuse cases are not prosecuted.

Our justice system relies heavily on the logical reconstruction of criminal activity, and much of what we know about sexual abuse doesn’t withstand logical commonsense analysis. It stretches credulity to imagine that a child could be dropped off at a daycare center in the morning, be fondled, sodomized, or subjected to bizarre rituals in the course of the day, and then say nothing about it to the parent who picks him up in the evening. In normal everyday life, if Jacob bites Jessica at lunchtime, Mom will hear about it the minute she arrives.

Why is it different with sexual assault? In cases of incest, experts and the public find it easier to understand a child’s desire to protect an abusing parent. But some aspects of a child’s reluctance to report abuse outside the family remain mysterious. It is known that most sexually abused children feel ashamed and guilty about their experiences, and the trauma itself may prompt them to block the memory. Also, the offending adults usually order children not to tell, and sometimes specifically threaten them with harm.

Specialists have learned they can unlock these secrets through the use of expressive tools for children such as puppets, anatomically correct dolls, drawings, and games – along with carefully constructed questions. “If you don’t ask the right questions, the kids can’t answer you,” says child and adolescent psychiatrist David L. Corwin of the American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children. “Recently I interviewed a little girl who had already told her mother about being molested, but when I asked, ‘Did anyone touch you down there?’ she answered, “No.’ When I asked, “Did he put his finger inside you?’ she said, ‘Yes, yes, that’s it,’ and then she told me all about it. But it wasn’t until I got the question exactly right.”

Even after telling, the child may retract his story – particularly if the situation gets tense, which it invariably does in repeated interviews with child protective services workers, police, therapists, and district attorneys. And even if the child is steadfast through the preliminary sessions, the trauma of facing the molester in court can be enough to cause him to retreat. “Kids are much more likely to lie by way of retraction than by making up the original story,” says Eileen Treacy. “Kids usually lie to get out of trouble, rather than to make trouble.

A child who first denies abuse, then discloses, then denies again provides powerful ammunition to the defense attorney who may charge that the leading and suggestive questions posed by the interviewers “seduced” an unmolested child into believing he was molested.

In fact, the issue of contamination by interviewers is always raised by the defense, even when there is clear-cut corroborating information. For instance, such charges were leveled against psychologists Laurie and Joseph Braga, who conducted interviews for the prosecution in the Country Walk daycare case in Miami, Florida. But in the Country Walk case, unbeknownst to the jury, the defendant had previously been convicted of child molestation. Furthermore, the defendant’s wife corroborated much of what the victims said, and his own five-year-old son had contracted gonorrhea of the throat under his care. The Braga interviews may very well have been suggestive, but given what else is known about the case, it’s improbable that an innocent man is now serving a minimum sentence of 165 years in prison.

Many people working in the field of child sexual abuse acknowledge that interviewers have contaminated the process by providing children with too much information, or have unintentionally asked questions in such a way that children, eager to please, have given answers they thought were correct. “In the process of learning about this problem, there has probably been some overreach in the past. But much of that has now been corrected through the development of guidelines for interviewing and evaluating child sexual abuse cases,” says Corwin, who chairs the group of committees addressing professional guidelines for the American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children.

Meanwhile, several studies have demonstrated that children are surprisingly resistant to persuasive questioning. One such study was conducted by Gail S. Goodman, Jodi Hirschman, and Leslie Rudy at the University of Denver. They videotaped 48 children, ages three to six while they received inoculation shots at a local clinic. Several days later the children were interviewed about their experience and asked such leading questions as, “Did she kiss you?” and “Did she touch you any place other than your arm?” as well as neutral, nonabuse questions. Out of the 48 children, only 3 said yes when asked if they had been kissed when, in fact, they had not been; other errors were errors of omission, such as when one child who got an inoculation said he did not.

Even if children are accurate in their descriptions of abuse, they may not do well when asked questions posed in adult terms. Children are more literal than adults. They don’t automatically translate “Were you in his house?” to “Were you in his apartment?” and their conception of quantity, as in “How many times did he or she do this to you?” is generally not precise. A child’s ability to pinpoint exact time and place is also limited. Charges involving over 30 preschoolers were dropped in a recent San Francisco case when the judge would not permit testimony from children who couldn’t state exactly what dates they were molested.

Many of these obstacles could be overcome, says Roland Summit, if judges would allow an adult in court to translate the lawyers’ questions into language children can understand. A child who can’t answer “How many times did it happen?” could probably answer, “Was it a lot of times or just a few?” A child who can’t remember a date may be able to remember if an experience occurred near a birthday, when school was out, and so on. “Anyone who has limited communication skills is ordinarily afforded an interpreter,” Summit says. “If a person is deaf you don’t throw out the charges. You bring in someone who signs.”

Cases are also frequently endangered when a child mixes reality with fantasy, even though the fantasy may be an emotional response to the trauma about which he is testifying. A typical example was in the case of a four-year-old child in California. There was fairly clear-cut physical evidence that the child had been sodomized. On the stand, in answer to questions about the abuse, he said, “Fred put his pee-pee into my butt.” But when he was asked what happened next, the child answered, “I picked Fred up and threw him out the window.” The judge threw the case out of court.

“What the child is doing in this situation is changing the end of the story to maintain his psychological equilibrium,” says Eileen Treacy. “Children have defense mechanisms just like adults, only more primitive.”

Many people believe that judges should allow all of a child’s testimony – no matter how inconsistent – and let juries evaluate the truthfulness. “So much of this has to do with education,” says Treacy. “When the way children think is explained, the inconsistencies are comprehensible to both judges and juries.”

When a case is tossed out of court, the public tends to equate the lack of conviction with proof of innocence, and many of the parties involved have their credibility severely damaged. Accordingly, as a result of public opinion, some judges have become even more arbitrary in disallowing the testimony of young children, and some child protective services have stopped aggressively investigating cases. Laurie and Joseph Braga say some interviewers now are so afraid of asking leading questions that they are unable to help children talk about their experiences.

“Yet there is a healthy side to the current scrutiny,” David Corwin says. “It has forced people to rethink their interviewing methods and to be cautious. The investigation of child sexual abuse is a new field of scientific inquiry. What is known is not widely known, and even the most knowledgeable can honestly err.”

Unlike many other crimes, child molesting is often compulsive and repetitive, and successful prosecution of sexual offenders is closely linked with the prevention of future abuse. Every time a sex offender walks away unprosecuted, many children are put at risk. The problem of protecting the rights of innocent adults is critical, but certainly the responsibility of protecting children is no less weighty.

As part of providing as secure a world as possible for our children, parents need to work for legislation that will promote courtroom procedures that safeguard the interests of adults and children. And the mental health professions need to develop effective treatment techniques for sex offenders. But until those improvements are made, we parents must maintain a degree of vigilance in our relationships with those who take care of our children, a vigilance that violates many of our dearly held values of trust and openness and generosity of spirit. If we are to protect our kids, we have no choice.

WHAT TO DO IF YOUR CHILD TELLS YOU HE’S BEEN ABUSED

If a child makes a statement like “Mr. Smith put his hand on my pee-pee,” it should never be ignored. Nor should the parent panic and immediately assume it’s true. Child abuse therapist Eliana Gil recommends that parents react the same way they would if a child said he had vomited blood: “Ask what was going on right before it happened, what time of day it happened, where and how it happened.”

“It’s a very provocative statement for a child to make,” says Gil, “and it’s certainly going to get a response. Kids can learn that saying some things gets more attention than others, so you have to be cautious. There are many possibilities. Maybe it happened and it was someone other than Mr. Smith. The main thing is to stay open to anything the child may have to offer and to check out as much as you can.”

After initial questioning, parents who suspect abuse should contact the National Child Abuse Hotline for advice and referrals to specialists near you: (800) 422-4453.

WHAT PARENTS CAN DO TO SAFEGUARD THEIR CHILDREN

When selecting childcare, there are a number of things you can do to ensure that you find a responsible caregiver. First, check references. Get the names of other parents whose children have been in the sitter’s care. Call each of them. Ask how well they know the caregiver. Ask them to describe the kind of person he or she is, and ask if they are aware of any problems involving their own or any other children

Once you’ve made a choice, get in the habit of dropping in unexpectedly. If ever something doesn’t feel right, trust your instincts and find alternative arrangements. Experts say it is unrealistic for parents to think they’ll be able to spot potential child molesters from any typical characteristics. Although some are childlike and obviously less comfortable with adults than with children, most are well-respected members of the community and difficult to categorize.

Most children who’ve been molested do not exhibit obvious physical traces, but parents should be aware of some behaviors that often accompany abuse. For example, a normally outgoing child may suddenly become withdrawn; or a child who has been molested may display excessively sexualized behavior, such as masturbation or sex play with other children. Excessive, according to therapist Eliana Gil of Gil & Associates, Pleasant Hill, California, “means a child will not be entertained in any other way. While some kids who have not been abused also display such behavior, it’s usually not with the same force or agitation..”

Gil recommends that parents simplify their warning message to their children to two parts: touching and keeping secrets. “The first thing I’d say is, ‘The private parts of your body are the parts you cover with underwear or a bathing suit. If anyone touches you on your private parts, let us know.’ The second warning would be, ‘If anyone tells you to keep a secret from us that means something is not right, and you must let us know right away.’ Two simple concepts. That’s enough.”

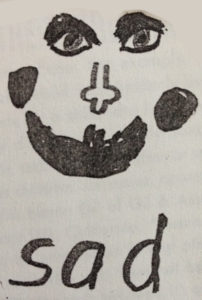

The child that drew this self-portrait was six years old. She had been molested by her father. The girl’s therapist interprets the image: “The makeup makes it a very sexualized picture. The child’s internal turmoil is revealed in the inconsistency between the made-up smile and the word sad.” |

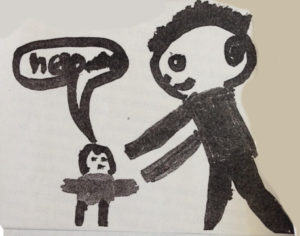

The five-year-old victim who drew this picture describes it in his own words: “He’s taking off my clothes. I feel sort of scared. That’s why I’m saying ‘Help me.’ He’s looking back to see if my mom’s coming.” |

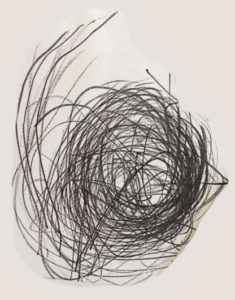

Pleasant Hill, California, psychotherapist Enid Sanders recalls a five-year-old patient who had been repeatedly sodomized: “I asked him to tell me how it made him feel. This drawing was his response – that and the words ‘It’s firecrackers going off in my mind.'” |