-

jew-ish: the life and times of a one-sixteenth jew

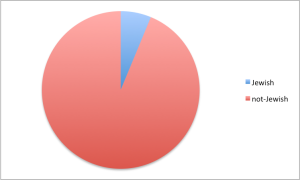

I am one-sixteenth Jewish. It’s funny to say it like that, but that’s what it comes down to on the family tree. And, I guess that’s how much Jewish I feel. One-sixteenth.

How exactly does that translate?

Most of the time I don’t feel Jewish, but I don’t feel not Jewish either. I feel Jewish-ish. Since my Jewish blood comes through my mom’s mom’s mom (otherwise known as my maternal grandmother), it would be enough for Israeli citizenship should I want it, and, as my mom pointed out, it would’ve been good enough for Hitler. Blood is what I’ve got to go on since all the women in my family coupled with gentiles and it’s an atheist line.

My mom once told me that the closest she could get to defining her Jewishness was that she gets a family feeling when she was around Jews. I feel the same, but I wonder if that counts. Doesn’t everyone get a family feeling around Jews? Sort of like the Italian mama in the neighborhood is everyone’s mama.

My mom’s mother, Naomi, now she felt Jewish. Her mother, Mama Sarah, fled the pogroms in Russia in the late 1800’s, travelling in steerage on an ocean liner bound for New York. Naomi was brought up kosher in Yiddish and spoke it with her first daughter but by the time my mom was born in Los Angeles 16 years later it became only a code language for adults to speak.

I don’t remember anything particularly Jewish about my grandmother except her overly-emotional attachment to what her family ate (but aren’t Italian and Catholic and Russian mothers known for that too?) It was actually my Irish Catholic grandfather (her husband) who tried to interest me in my Jewish roots.

Despite the fact that he had once studied for the Catholic priesthood before thinking better of it, he had a great appreciation of Jewish scholarship. One year when I was probably 12, he gave me “The Jewish Book of Why” as a Christmas present.

My first question was: Why would I want to read this book? I didn’t know enough about the traditions to have any unanswered questions. I still have the book and I still don’t know what a rimmonim is.

One of my earliest impressions of what it meant to be Jewish in my family was formed by an account of an event that happened twenty years before I was born. No, I know what you’re thinking, it wasn’t the Holocaust. In 1955, my grandparents took my mom and my uncle out of school for three months and embarked on a grand tour of Europe. Well, as grand as you can get in a used VW bus with a tent. One of their stops was Pisa, Italy. For some reason my mom and my grandmother split up from my grandfather and uncle for the morning, meeting up later for a tour of the famous leaning tower and the neighboring rotunda. A German woman in her fifties who was travelling alone asked my grandfather if she could join the family for the day – maybe she was lonely or felt self-conscious. My grandfather welcomed her.

Upon reuniting, however, my grandmother, a famously difficult and passionate person, didn’t like the looks of this German woman. The war had only been over for ten years but this woman had done more than merely survive. She was clearly prosperous – she was traveling in Italy on her own.

At one point in the tour, the guide explained the unique echo the cylindrical rotunda produced. Anyone saying something from a certain spot in the room could hear their voice reverberating throughout. After the guide demonstrated the effect, my grandmother asked if she could try. Looking straight at the German woman, she called out, “Ich bin ein Jude.” (I am a Jew, in perfect German.) The German woman turned on her heel and left the tour.

At one point in the tour, the guide explained the unique echo the cylindrical rotunda produced. Anyone saying something from a certain spot in the room could hear their voice reverberating throughout. After the guide demonstrated the effect, my grandmother asked if she could try. Looking straight at the German woman, she called out, “Ich bin ein Jude.” (I am a Jew, in perfect German.) The German woman turned on her heel and left the tour.This episode, recounted to me by my mother when I was young, stuck with me. “I am a Jew” echoed not only in this small chapel, but into Northern California in the mid-eighties when I was starting to be old enough to think about who I was. It taught me that being Jewish meant being brave. Being Jewish meant embarrassing your family. And, being Jewish meant visceral suspicion of all Germans.

It must not be a coincidence, then, that the time I felt the most Jewish was when I disembarked from a plane bringing me to my then-boyfriend’s hometown in Austria a few years ago. The moment I saw the “Eingang” (entrance) sign at the airport I felt a yarmulke sprout up on the back of my head (I know, I know, women don’t wear yarmulkes…). I didn’t declare my Jewish roots to any of the airport authorities, but it was the first time in my life I felt my grandmother’s spirit rise to the surface, on guard in my new setting.

Maybe being immersed in a German-speaking environment for the first time makes everyone feel Jewish whether it’s in their blood or not. Most Americans in my generation had our first exposure to German and German-speakers through World War II movies – hardly a gentle introduction.

My grandmother’s voice was called back to the surface a couple months into my stay in Austria. My ex-boyfriend and I were at a flea market in the countryside. As we turned the corner on the next row of stalls, I saw a framed portrait of Hitler hanging prominently in the memorabilia stand next to the vintage button lady I had been eyeing for button bracelet supplies. Can I say I felt my blood chill without it sounding like too much of a cliché? That’s what it felt like.

My boyfriend took one look at my gaping mouth and one look at the portrait and, perhaps sensing the Great Voice that was about to emerge, steered me in the other direction. In the moment I was completely consumed with questions about what the possible meaning and permissibility of such a display would be in modern Austria. (Unfortunately my befuddled, defensive boyfriend had no good answers for me -“It’s just a historical item” – and I had to take it up with my human rights friends who said in no uncertain terms that farmers in that area were provincial Nazi-sympathizers.)

Later, I fantasized that instead of hurrying away, I would go up to the nice-looking couple manning the booth and channel my loudest, clearest Naomi voice and declare “Ich bin ein Jude,” looking at them straight in the eyes. I wanted to embarrass them and everyone who had walked by the portrait. I wanted the whole flea market to know that I knew their dirty not-so-secret secret. The idea that there was still anti-Semitism in the area just 15 kilometers from Mauthausen, Austria’s worst concentration camp, wasn’t shocking. The idea that it could be so brazenly displayed was. For the rest of my time in Austria I no longer felt one-sixteenth Jewish – I was 100% Jude.

My most recent time in Europe, however, revealed a much more fair-weather friend side to my Jewish identity. This Fall, I spent six weeks in Antwerp, Belgium. As well as being a charming, perfectly-sized city/town, Antwerp is home to one of the largest communities of Orthodox Jews outside of Israel. The neighborhood I was staying in was the center of the ultra, uber, super Orthodox Jews, called The Haredi. The Haredi men dress in black with long beards, ear curls and top hats. The women wear wigs to hide their hair, long skirts and generally dark-colored conservative clothes. All the stores and restaurants are closed on Saturdays.

Most of the time I’ve spent living in Europe – in Italy, France, Holland and Austria – Jews have been conspicuously absent. In Italy I knew exactly one Jew and the only reason I knew he was a Jew was because it was so unusual that everyone mentioned it when they referred to him. The obvious explanation is that there are very few Jews left in most parts of Europe because they either fled or….were killed.

Seeing a thriving Jewish community in Antwerp was a nice change. World War II could go on the back burner and I could focus on what was there instead of what was missing. I was hopeful that my time there would spawn a meaningful connection with European Jews that would cement my Jewish identity. It didn’t work out that way.

During my stay I found out that most Europeans, especially Russian Jews, came through Antwerp on their way to America. Two million European dreamers set sail from the port (one of the largest in the world) between 1873 and 1934, when the Red Star Line operated. This means that my great grandmother, Mama Sarah, most likely passed through the neighborhood I was staying in, probably being hosted by long lost relatives of the Orthodox Jewish families I passed every day (many of the Haredi have Russian roots.) This was great progress – that meant the city has part of my history and is the closest I’ve been to my Jewish roots. Forget a family “feeling” – these Jews could be my real family!

On one Sunday, the city of Antwerp opened cultural institutions for the public to view. My boyfriend and I visited the neighborhood synagogue, established in 1913. As part of our self-guided tour, we climbed up the narrow spiral staircase to see what the view was like from the balcony level. The view, it turned out, was no view at all. In front of the rows was a long panel of frosted glass so that no one on the balcony could see down on to the main floor (where everything actually happens) when either seated or standing. This, it said in the leaflet, was the women’s gallery.

I’m not an Orthodox scholar (see: unread “Jewish Book of Why”) so can’t explain the justifications for such separate and unequal synagogue seating, but that glass cage conveyed pretty clearly to me my second-class status in the eyes of the Haredi. The only similar architecture I could remember was the balconies that American Blacks had to sit in in courtrooms in the 1950’s. At least they could see the proceedings below!!

Now, I’m no naïf when it comes to cultural gender divisions among religious and traditional communities. When I worked in a Somali refugee camp I had to train my female and male health educators separately. In Darfur, I never shook the men’s hands when I welcomed them to my meetings. And, in Texas, when I was interviewing male legislators I got used to them calling me sweetheart. But these Antwerp Jews were supposed to be my people.

Sitting up there, looking into a wall of glossy nothingness, however, I had to again revise my Jewish identification level. Whereas in Austria I had been 100% Jude, there in Antwerp I was back down to a small fraction of Jewish-ish-ness. There was nothing about this set up that felt Jewish to me. Jews are the ones that fought for civil rights in the ‘60s, risking their lives to insist on change alongside Blacks in the Deep South. Jews are the ones who fought McCarthyism, who always fight for the underdog. How could I ever connect the dots between those Jews I grew up admiring, proud they were in my tribe, to the ones making me and my sisters sit behind the glass wall? No wonder Mama Sarah fled to America.

I guess the main thing to focus on here is that it’s a good thing that there are still enough Jews in the world to have such extreme diversity. And that I finally have an answer to what it means to be one-sixteenth Jewish. It means that when Jews do something I like or are persecuted, I’m Jewish; when Jews do something I don’t like, I’m not. On a scale of one to ten, how Jewish does that sound?

I’ve been conducting a genealogical quest of my roots and recently met someone who shared 1/16 of his DNA with me. I’ve written about him on my blog under “Adventures on Road X.” It is disheartening to look into the face of a 1/16th and see very little of what you’d see in a mother or father. But at the same time, it highlights my connection with everyone else in the world. By the way, I’ve been reading a book on 1900 Russia, and the rich tended to inflame the pogroms whenever the revolutionaries started gaining steam. They saw it as an escape valve for the poor’s frustrations.

[…] As I drove home from that night I thought about my mother. She was a compassionate woman who was warm and welcoming to nearly everyone but who harbored an almost unshakable hatred for Germans. I say “almost” because she felt sympathy for ordinary Germans who suffered during World War II. But when she encountered Germans who got through the war with their wealth and health in tact, she considered them either directly or indirectly responsible for the slaughter of six million of her tribe. (see Caitlin’s blog post jew-ish: the life and times of a one-sixteenth jew) […]

Just wanted to say, I really enjoyed reading this, as I’m one-eighth Jewish. (My mother’s mother’s mother) There’s very little out there that gives any voice to the unique experience of our group, which is bound to have a mix of genuine interest and “fair-weather” qualities, regardless of intentions. Too often people get on their high horse and say “you’re not Jewish,” but that’s not really true. Something is there. In some ways, It makes for an interesting comparison to people who have distant Native American ancestry. Anyway, very interesting and nice job.

Thank you! And, I must correct my math! My brother pointed out that we too are one eighth Jewish. How embarrassing. But I totally agree that there are many similarities with others with mixed heritage that don’t quite fit perfectly into any group.